Humans have always been weird and messy. And gross and perverted and funny and stupid and childish and selfish and insecure and eccentric. I love to think of the humanity, the human-ness of history. It makes me laugh to think about an 18th-century French aristocrat, thinking you were waving to them and then realizing too late that you were waving at someone behind them. There is so much pomp and circumstance, so much grandeur and elegance to the artifacts we are left with, and it is of the utmost importance to remember that the people who were around during those times were just that: people.

My most recent obsession really encompasses this dichotomy of grandeur and ridiculousness. I spent the summer playing around with knit imagery for a new Rudie sweater (launching in like 2 weeks!?), and I found myself doodling one thing over and over: a rampant lion.

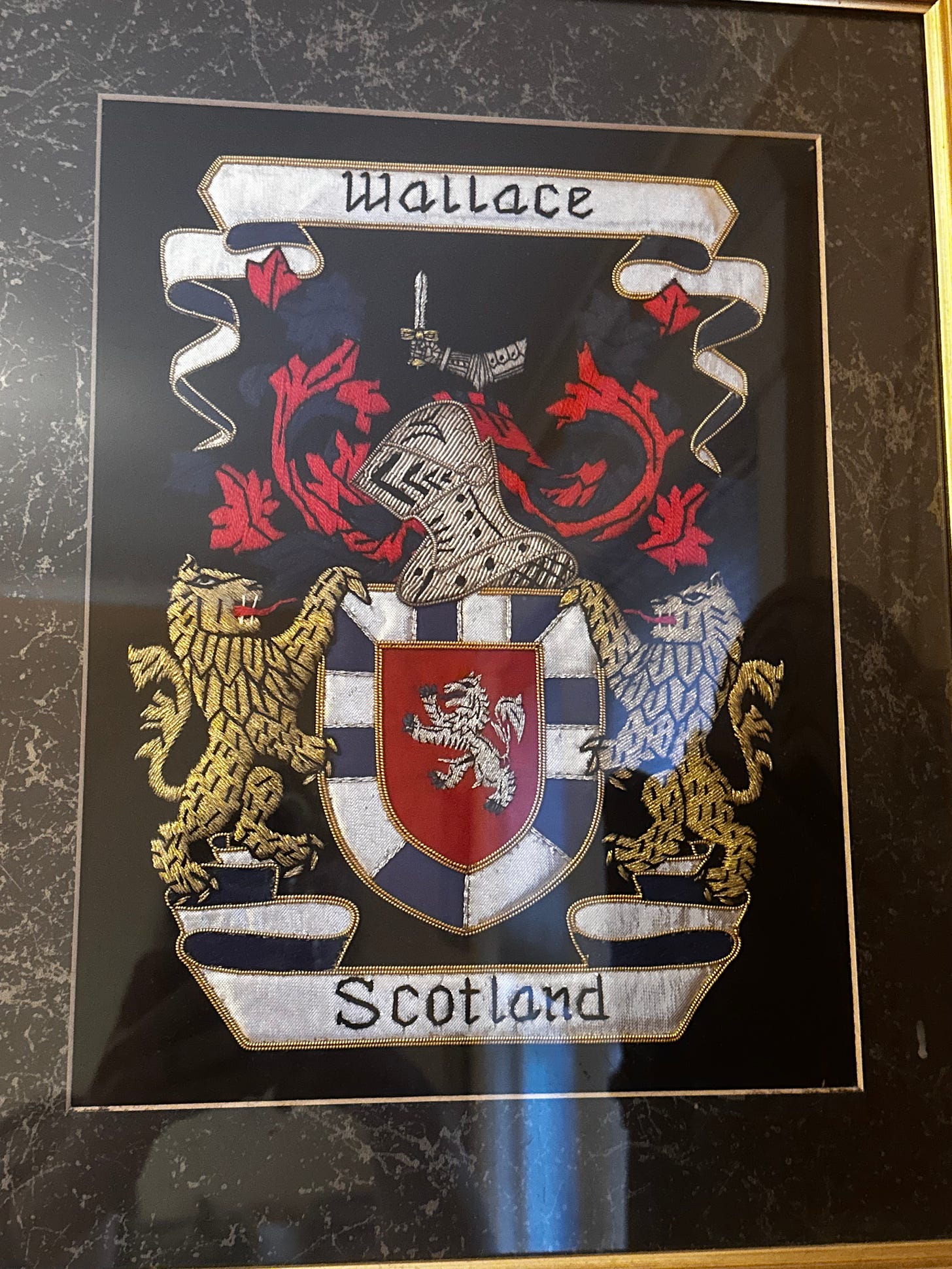

Traditionally it’s an anatomically incorrect upright lion, teeth bared, tongue outstretched, claws at the ready. I grew up with a few of them in the house, hanging around on our framed family crest:

Last Winter Nico and I found this shield on York Blvd and brought it home. I thought maybe it was an anthropomorphized Scottish artifact that made its way to Los Angeles to present itself to me, but it is actually just a prop from a movie.

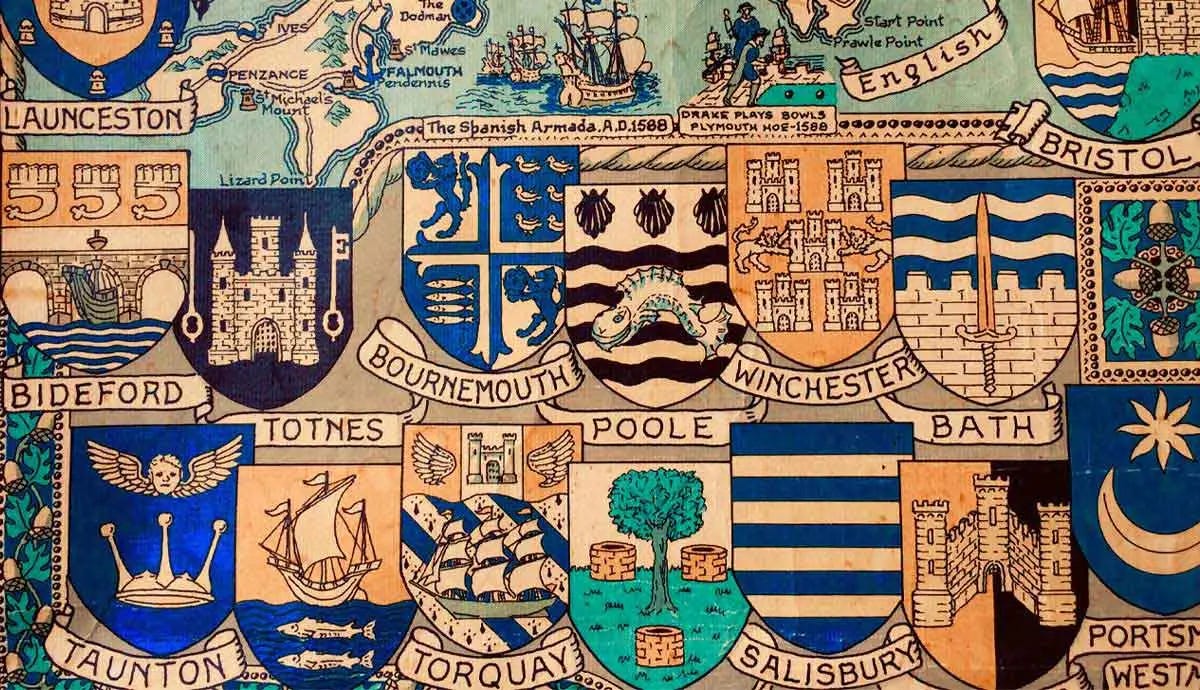

The rampant lion is one of a few common images used in heraldry (noun. /ˈherəldrē/ the system by which coats of arms and other armorial bearings are devised, described, and regulated… stay with me.) Some other common characters are unicorns, wolf heads, towers, swords, dragons, all kinds of cool stuff. It is essentially the medieval concept of familial logos.

Heraldry was initially used to easily identify royalty and important persona on the battlefield since their faces were blocked by their armor. And of course, since humans love to adorn themselves, they became more colorful and ornate with time.

By the 12th century, heraldic imagery was used in advertisements for upcoming jousts and events, so that even if you couldn’t read, you knew who was on the docket. Regular, non-royal families drew up their own coats of arms, and a sort of heraldic language developed. Not only could you communicate your familial lineage, but also what was important to you. Your company values, or whatever. The use of black meant your family valued wisdom. Green meant abundance and joy. Red was the symbol of the warrior and the martyr. Blue meant you valued faith and chastity. And of course, OG Rudeletter readers will remember, purple meant royalty, majesty, and sovereignty.

With so many family logos about, the role of Herald of Arms emerged. This person was responsible for keeping track of the designs, in some cases with official registration protocols. Families used heralds to assist in combining their coats of arms when they were joined through marriage. Heralds settled disputes between groups who felt that their coats of arms were too similar. And as is human nature, they created formalities regarding who was allowed to use what imagery and when. You could not register a coat of arms with say, a pink tie-dye background and a raccoon holding up a middle finger. There were rules. Heralds also did things like pass messages across battle lines, study enemy genealogy, and were granted a diplomatic immunity of sorts. They’re cool. But they’re not what we’re talking about.

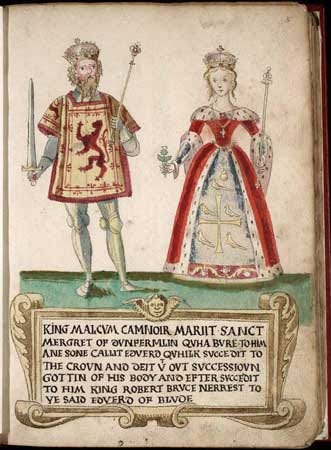

The rampant lion became emblematic of Scottish identity in particular. It was common imagery in the country since Malcolm III (King of Scotland from 1058-1093. You may know him from the play Macbeth.) He enjoyed the iconography of the upright lion and used it on his official seal. Quick but important aside: Malcolm was nicknamed “Canmore” and took it on as his surname. In medieval Gaelic it was more like ceann mòr, which means Big Head. Lol.

Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and honestly… much of the rest of the world… have a complex history with England, and it’s hard to pinpoint when exactly they fell to English rule. The general consensus is that the Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Wales, Scotland, and some of Ireland), relatively close to how we know it to be today, was formed in 1707. For reference, that is 500 years after the movie Braveheart takes place. Shit has been rocky for a long, long time. Anyway. Stay with me!!

In 1801, the monarchy created The Royal Standard of the UK, which is basically a flag-shaped coat of arms to symbolize the unity of the different countries under one kingdom. It included the rampant lion for Scotland, the Guinness logo harp for Ireland, and two boxes for the triple lion of England. And nothing for Wales.

In a twisted but classic move, flying the rampant lion flag separate from the Royal Standard began to be considered treasonous to England. Very All Lives Matter of them. Only “official representatives of the monarchy” were allowed to fly the rampant lion, and only when it was in concert with English imagery. This continued into the modern era. In 1978, a linen merchant in St Albans was fined £100 per day for putting the rampant lion on decorative bedspreads. I don’t have a primary source for this but a few different articles reference it. So I am choosing to believe it’s true and I am appalled.

Currently, the monarchy allows small representations of the rampant lion, but only when it benefits the tourist economy. You can enjoy a little postcard, you can purchase a refrigerator magnet along with a “Finding Nessy” t-shirt, or even wave a tiny flag at a parade if you MUST. You can enjoy Scottish heraldry in ways that are cute. But display it grandly and singularly, and you are an enemy of the state. So stupid.

Want to wear one yourself? Check out our Rampant Lion sweater here.

Get early access to articles like these in your inbox by subscribing to Ruby's Substack (it's free!)